Keith Knight: Informing America One Cartoon at a Time

July 28, 2017

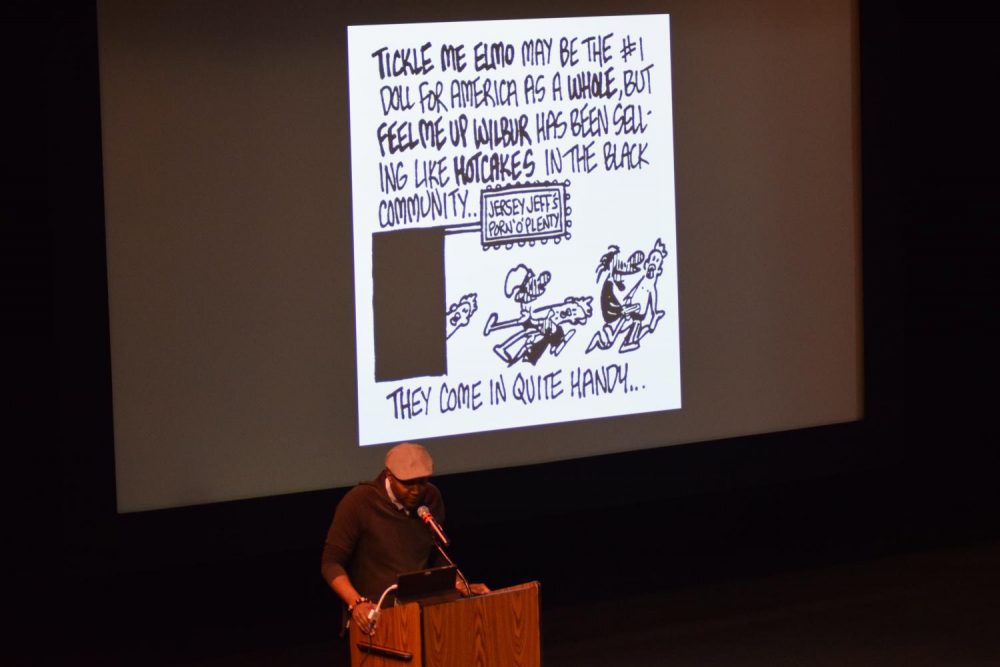

When cartoonist Keith Knight came to visit Prep in May, he met a lot of students who couldn’t decide whether they should laugh or cringe at his art. Though that reaction may be uncommon for some artists, Knight’s cartoons, largely focused on issues of race in America, with an emphasis on police brutality, often call forth mixed emotions from audiences. “Yes,” he confirmed. “Laughing and cringing. And hopefully thinking.”

Knight certainly puts significant thought into the subject matter of his work. He explained, “It sort of grew from police brutality into this thing about race and how important it is for people to understand how important the black experience in America is, and how we don’t learn anything about it.”

Some of the things Knight covers include the issue of how police “nickel and dime” minority communities, how black people get stuck in the prison system, wealth inequity stemming from the time of slavery, and the importance of all Americans acknowledging their participation in a racist system. He said, “I want to use my comics to explain this stuff in a much simpler way. Comics are sort of the court jester of modern day, which is we explain these complex issues in, hopefully, simpler and humorous ways to inform people on stuff that’s going on.”

Raised in Malden, Massachusetts, Knight was encouraged to be creative from the beginning. He described how he had one black teacher in grade school, a substitute who was an aspiring cartoonist: “he would sit at the front of the class and doodle, and I would bring my chair up to his desk and sit next to him, and then we’d doodle together, we’d just talk about how we draw different things. But just the idea that someone that looked like me wanted to do what I wanted to do meant the world to me. It was like a huge, ‘Oh, I can do this.’”

In high school, teachers continued to encourage Knight to follow his passion. In his junior year English class, his teacher allowed him to do his report on Animal Farm in the form of a comic strip. “It was all the high school students taking over my high school, and I was the head pig, I was Napoleon, and so we kicked out the teachers and did ‘under eighteen good, over eighteen bad’ all the rules and stuff like that, and I did caricatures of all the the teachers, so it was ripping on all the teachers. My teacher loved it so much he left it in the teacher’s lounge for like a week and a half,” he explained. “Really, I was encouraged the way every child should be encouraged to follow whatever they do, because I know what it’s like to see people not be encouraged to do it.”

Knight went on to college in Salem, Massachusetts, where he met his first non-substitute black teacher, who taught American Literature. “He assigned us Maya Angelou, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and when someone brought up the idea, ‘Why are you giving us all black writers?’ He said, ‘I’m giving you all American writers.’ That blew my mind. My art went from about keg parties to about being black in America.”

Throughout college, Knight continued drawing with a job as a caricature artist at Faneuil Hall in Boston, as well as doing comics for the college newspaper and posters for bands, events, and the college radio station.

After college, his friend, another cartoonist, convinced him to move out to San Francisco, where he lived for about sixteen years. When Knight got there, he said, “I drew for local magazines and stuff for free there, and then I got into the local newspaper, and then after three months, I got into the daily newspaper, and then I just started self-syndicating.”

Chuckling, he continued, “Early on, when I just started, I would just get hired in February, which was black history month, like the bigger gigs. I would do it, I would make sure I got paid and cash the check, and then I would write to them and say, ‘I’m free the rest of the other eleven months.’”

For all that is fed to young people about how hard it is to make it as an artist today, Knight’s story seems almost miraculous. He doesn’t really see it that way. “I think for me,” he said, “I’ve always just had that idea, why wouldn’t you just go for what you wanted?” Knight shared some advice he gave to a an aspiring cartoonist who asked him if she should go to art school. “She told me how much it cost to go there, it was like $40,000. For a year. And I said, ‘No! No, no, no, no!’ I said, ‘Save $10,000, go overseas to Europe, and just travel around, and then just draw cartoons about it. Like, just draw cartoons. That’s it. That’s the experience. There’s no reason you should drop 40 grand to draw cartoons, in no way, shape, or form. If you draw cartoons, you will get better. You just do it, and you will get better, and you put in that time. It doesn’t matter what degree you have, it’s just how much time you put in, and how much you want it.’”

It was in talking about race in America that Knight found his voice. “I sort of knew that no one’s really doing cartoons about these race issues or anything like that, I’ll become that thing. I took this business class that sort of taught me that, and it’s really weird because I was in this class with all these business people, and they were sort of surprised, like, ‘What is this weird creative guy doing?’ But it taught me a whole lot about, become that thing that everyone didn’t think they needed but they actually do.”

Knight, through funny but honest comics, continues to try to remind people that racism is still prominent in American society. “There’s this idea that, eh everything’s equal, get over it, that was a long time ago. The residuals of that, which is only 150 years ago, resonate today. When you have a black history museum in Washington–the woman that opened that up, her dad was born a slave. If your dad was a slave, that’s still here. That’s totally still here.” Seeing the looks on the faces of the students who listened to Knight’s presentation on police brutality, it is clear that a few people are getting the message.